Speaking with Substrates

|

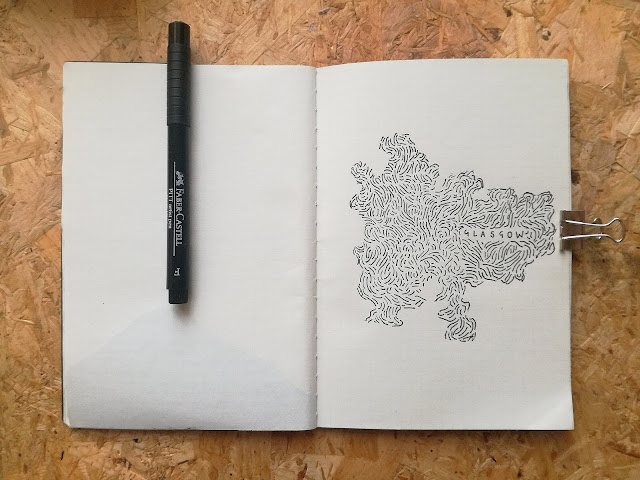

| Embryonic Glasgow, fine-liner drawing in sketchbook, April 2020 |

After a substantial pause, I move away from the tenement housing and towards the Clyde. This is where I started my climb of the High Street, and where I was first transported to Medieval Glasgow. Withdrawn from my own period of April 2020 and redeposited amongst multiple time periods, I have become stretched and sagging in composition. My body no longer resembles that of a 28 year old woman. Moving more like a swathe of indeterminate specks, I have become a dissolved entity with the ability to move through space unseen, unheard and uncomprehended by those around me. Over this period, I have become more matter than human.

Becoming, and then existing as, a swathe of specks has removed my anthropo-mastery over the land that has made up this jaunt. High Street has become more than space and place; it is a plateau of tugs, shifts and pulls, of multiplicity, being-within the ideological containment of specific human actions. By fragmenting in this way, I too have become re-movable; a mound of spoil; a deposit of scintilla moving between sites, leaving traces here and there. To think of myself as an not-quite-human entity in this way is allowing me to embrace material intimacies that cause seepage amongst boundaries of definition. It is to think of an area as an arena.

I fall into place by the banks of the Clyde. The era I am in has shifted to the 1970’s and the tug of post-industrial boom is pulling buildings down. Thatcher’s hand is visible in the removal of the ship-building industry and the grinding to a halt of coal, iron and steel mines within greater Glasgow. The local newspapers paint an ugly scene of the area, in which gloom spills forth from most of the streets’ orifices in the East End. Those streets, wynds and riggs that already existed in the lack, (in the lack of space, in the lack of sanitation, in the lack of wealth, in the lack of socio-economic support) are now folding in upon themselves through the process of decay. Entropy too stakes a claim within these sites of lack.

Over 30, 000 people were displaced from the East End houses during the sixties. Families, pushed away from their communities and their overall understanding of city living, were put to live in flats and houses in newly developed schemes on the outskirts of the city. Easthouse was further to the East, a mass of grassland and rows of housing stretching into the distance. These people had too been removed, perhaps seen as ‘spoil’ by the council due to their economic status. What was clear during this time was that the whirling dust of entropy - a gradual decline into disorder - was in the winds that passed between those purpose-built homes. By clearing the land by Saltmarket, on the adjoining streets to High Street, and on Rottenrow, they changed the fabric of it. Acting in this way was about removal. But as Karen Barad writes, there are always traces, and there is never no-thing left.

The high rises that sprouted across the city during the planned housing boom were slowly condemned as unfit for human life. The people within the flats had formed new communities, however the shiny enterprise of these schemes soon peeled off like cheap varnish in the sun. Buildings were flat-pack made, designed using sheets of concrete that would later become the opposing structures dotted around the outskirts of the city. Concrete, a composite of aggregates and cement, seemed an ideal material for building on a budget and easy to coat in fire-proof asbestos. The construction of pre-fabricated housing, consisting mainly of large cast concrete panels made elsewhere, became a means to clear out the neighbourhood of the dirt and grime appearing to congest it. Alas, the Glasgow Corporation, and therefore the government, did not look after the people or the flats. The estates crumbled, and many were demolished after becoming collapsing blocks of matter, such as the 1968 incident at Ronan Point in Canning Town, London. Once again a spoil had been removed and displaced; once again fragments of speech, laughter, conversation and life were left in mounds across fenced off demolition lots. I’m interested in whether traces like this can become relics.

In 1968 Shelter Scotland, the housing charity, was also formed.

Matter gathers in pockets across the city. Although you have been following me as a spectre to the High Street, I know of many places where matter has gathered in various forms. Sometimes the people and places of history are reflected in bronze and stone through monuments. The humans and more-than-human-others that create the thread of life through the sprawling city are often the ones left out of its planning, and therefore, the being of that city. I have visited the High Street because I wanted to get to know what it was made up of. Streets are always more than tarmac and Costcutters. Stories are buried beneath our feet, matter-ed in, as, and with substrates.

Now, within my time-travel, I have taken the final form of displaced matter. Matter-ing, as our friend Karen Barad frames it, is about materialising the lens. Extending vulnerability in this way allows humans to re-negotiate their own self, and in turn this leads to ushering encounters of care with ourselves, other humans, and our surroundings.

|

| Spoils, fine-liner drawing in sketchbook, April 2020 |

Comments

Post a Comment